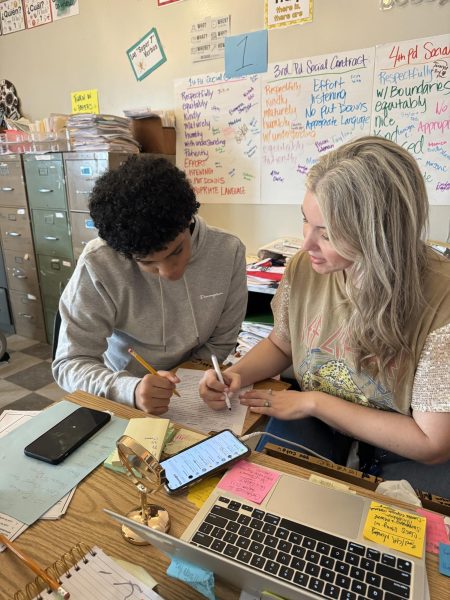

Permanent sub from Jamaica lets her accent do the talking

Joan Kelsie, one of three permanent subs at Tupelo High School, points to her county of origin on the map.

December 17, 2015

“Hey, we got that Jamaican sub!” That’s usually what Joan Kelsie, a permanent substitute at Tupelo High School, hears when students walk through the door at the beginning of a block. If a student doesn’t know about her nationality or why she’s such a curiosity to others, they find out as soon as she opens her mouth.

“People here absolutely love my accent,” she said. “If I’m not careful, I’ll spend the whole class answering questions about Jamaica.”

Kelsie, a former regular sub, has been one THS’s three permanent subs for nearly two years. She said the transition was difficult, but she has adjusted well.

“Now I look forward to weekends like never before,” she said.

Although she is a sub, Kelsie has more than 10 years of teaching experience up her sleeve, even with two years of working at a juvenile detention center. She started straight out of high school, or “secondary school” in Jamaica, as a pre-trained teacher with aspirations to be a college professor.

“A pre-trained teacher would be the equivalent to a student teacher here in the States,” she said.

During her time as a pre-trained teacher and her five years teaching high school, she mastered her teaching skills, even teaching students a couple of months to a year younger than her.

“One of my best memories was teaching my younger sister,” Kelsie said. “She’s only two years younger than me.”

She thinks that kids here and in Jamaica are the same yet very different.

“I was in the classroom a long time ago,” she said. “I’m sure a lot of changes have happened since. It was a different culture there. Education is seen as a vehicle to move you out of poverty or to help you achieve and move up the social scale. The emphasis was very different.”

Growing up in a poverty stricken background, education was the only way out for kids in her community. Usually children had an ultimatum for their future: succeed in school, move to the city and make a career for yourself, or stay in the rural areas and help your parents farm. Since Kelsie said Jamaicans have a “learn or die” mentality, children there tend to be much different from most of their American counterparts since school is mandatory.

“Children are so blessed here,” Kelsie said. “Educational opportunities in third world countries are not as available as they are in America.”

Even though Kelsie is a teacher with years of experience under her belt, she isn’t one of those uptight, stuffy old substitutes. She still jokes with students and makes them feel comfortable with her. Usually class starts with a long Q&A about Jamaica followed by stereotypical marijuana and dreadlocks questions. Once she finally calms the steady flow of questions from eager students, she puts them to work. Most students at THS know about Kelsie by now and have come to love and respect her.

“I think having a teenage son myself definitely helps me understand students here, especially boys,” she said.

In the end, Kelsie said, she just loves teaching. She comes every day ready to have a positive effect on the life of any student she encounters. After all, it’s been her dream job since high school.

“It’s one of the most rewarding things to take a child from point A to point Z, and you look back and you realized that you were instrumental in moving that person along,” she said. “There is no limit to climbing the ladder of success, as long as you’re educated.”